By Peta Riles (Corporate governance and administration)

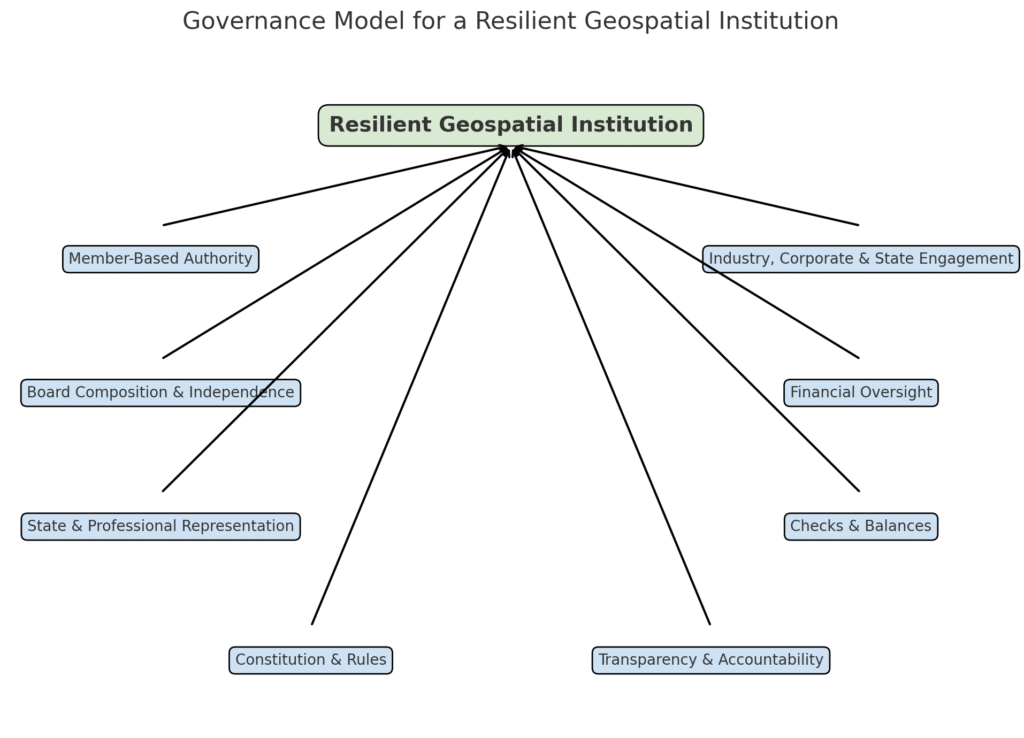

The collapse of the Geospatial Council of Australia highlighted a critical lesson for the profession: strong governance and financial oversight are essential, but they are not enough on their own. A sustainable institution must also be built on broad engagement that gives legitimacy and resilience. A future body should be member-driven at its core, while also establishing formal mechanisms that bring in perspectives from industry, corporate partners, and state associations.

At the heart of such an institution are its members. Individual professionals form the core, and their authority should extend to strategic and extraordinary decisions made through annual or special general meetings. This includes board elections, constitutional amendments, budgets, and major policy directions. Structured advisory councils and committees should feed into the board, ensuring that proposals reflect the breadth of the profession before being put to the membership for approval.

Industry, corporate, and state-based associations also play a vital role. Their expertise, sectoral knowledge, and ability to identify risks enrich decision-making. By participating in advisory councils, project committees, and consultation mechanisms, they contribute meaningfully without undermining the legitimacy of a member-led system. The balance lies in ensuring they have influence but not voting rights.

The board itself must embody both independence and expertise. A structure of seven to nine directors, including two to three independent directors with strong backgrounds in finance and governance, would strengthen oversight. The board’s role should be distinct from operational management, focusing on strategy, fiduciary responsibility, and risk. A dedicated treasurer or finance director should monitor budgets, report transparently, and chair the audit and risk committee. Regular financial updates to members would enhance accountability and ensure that risks are identified early, a safeguard made urgent by the lessons of the GCA collapse.

Representation at both the state and professional levels is also essential. State committees would preserve local and regulatory connections, while specialist advisory councils—for surveying, GIS, remote sensing, and other areas—would provide structured guidance without overloading the board. Term limits for directors encourage renewal and prevent entrenchment, while conflict-of-interest registers and annual disclosures guard against misuse of authority. Independent audit and risk committee reports should go directly to the board and be made accessible to members through annual reports.

A clear and transparent constitution underpins the whole system. It should codify membership criteria, board structure, officer roles, election processes, meeting requirements, and dispute resolution procedures. By clearly demarcating member authority from advisory input, the constitution ensures continuity and stability. Transparency is further reinforced by the annual publication of audited financial statements, governance and risk statements, and records of board decisions. Regular member forums would keep dialogue open and maintain alignment with the profession’s needs.

By combining member-led voting, structured stakeholder engagement, independent expertise, and robust financial oversight—underpinned by a clear constitution—this model offers simplicity, resilience, and inclusivity. It balances legitimacy with accountability and ensures that the institution remains responsive to the wider geospatial sector. In doing so, it lays the groundwork for a professional body that can endure and provide lasting value for its members and the broader community.

Leave a Reply