Dean Howell

This article was originally published in Linkedin

Australia’s geospatial community has always been shaped by collaboration, innovation, and a drive to stay relevant as technology advances. The recent receivership of the Geospatial Council of Australia (GCA) has left a significant gap, both symbolically and practically, as Australia no longer has a unified professional or industry association for the mapping, GIS, and spatial sciences sector.

To understand how we reached this point, it’s important to look back at the associations that shaped the sector, and the path of mergers and transitions that ultimately created GCA.

The Early Foundations: Surveying & Mapping Bodies

The origins of Australia’s professional representation in the geospatial sector lie in surveying and cartography.

- The Institution of Surveyors Australia (ISA) was one of the earliest national professional bodies, representing surveyors across disciplines and states. Its focus was on education, professional standards, and recognition of surveying as a regulated discipline.

- Cartographers established their own national body in 1952, the Australian Institute of Cartographers (AIC), representing the craft and science of mapmaking. It changed its name to the Mapping Sciences Institute, Australia (MSIA) in 1995.

These organisations reflected the traditional backbone of spatial sciences: surveying for accuracy and land management, and cartography for the representation and communication of spatial information.

Expanding Horizons: GIS, Remote Sensing & Urban Information Systems

From the 1970s onwards, Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and Remote Sensing began to reshape how Australians worked with spatial data. As new technologies emerged, new specialist organisations followed:

- Mapping Sciences Institute, Australia (MSIA) grew from the cartographic community, broadening into GIS, photogrammetry, and spatial data management.

- The Remote Sensing and Photogrammetry Association of Australasia (RSPAA) catered to academics and practitioners using imagery and aerial survey methods.

- The Australian Urban and Regional Information Systems Association (AURISA) was the local arm of URISA (Urban and Regional Information Systems Association), which had been founded in North America. AURISA gave GIS and spatial information professionals a voice in Australia and New Zealand at a time when digital mapping was in its infancy.

This period saw the industry diversifying rapidly – from traditional surveying into the wider spatial sciences.

The First Consolidations: From URISA and ISA to SSI

By the early 2000s, the sector faced fragmentation across multiple overlapping associations. The first big move towards unification came in 2003, when:

- The Institution of Surveyors Australia (ISA),

- AURISA (the Australian Urban and Regional Information Systems Association, linked to URISA), and

- The Remote Sensing and Photogrammetry Association of Australasia (RSPAA)

all reconstituted themselves into the Spatial Sciences Institute (SSI).

The new SSI represented a landmark moment: for the first time, surveyors, GIS professionals, photogrammetrists, and remote sensing specialists were housed in one professional organisation.

From SSI to SSSI

While SSI created a broader professional body, tensions remained around governance and representation. Some state divisions of ISA (such as in Victoria) were uncomfortable with the transition, and re-established independent entities like the Institution of Surveyors Victoria (ISV) in 2007.

Nevertheless, in 2009, SSI formally merged with the remaining Institution of Surveyors Australia to form the Surveying & Spatial Sciences Institute (SSSI).

This was a watershed:

- Surveying (a regulated profession) and the broader spatial sciences (GIS, remote sensing, cartography, etc.) were united nationally.

- SSSI became the peak body for individual professionals in Australia’s geospatial sector, providing certification, professional development, and representation.

Industry Representation: The Role of SIBA

While SSSI focused on individuals and professional standards, the business side of the industry needed its own voice. That role was played by the Spatial Information Business Association (SIBA), which represented companies, consultancies, and vendors.

SIBA advocated for industry growth, government partnerships, and the economic importance of geospatial solutions. Later, SIBA partnered with the Geospatial Information & Technology Association (GITA ANZ), strengthening its role as a commercial and business voice.

By the 2010s, the landscape had stabilised into two clear entities:

- SSSI – representing professionals.

- SIBA|GITA – representing businesses and industry.

The Birth of the Geospatial Council of Australia

By the late 2010s, there was widespread recognition that two separate associations still left the sector fragmented. After years of discussions, SSSI and SIBA|GITA merged in 2022 to form the Geospatial Council of Australia (GCA).

The GCA was ambitious in scope:

- A single body for professionals and businesses.

- A unified voice for advocacy to government.

- A hub for professional development, training, networking, and certification.

It was designed to be the “one stop shop” for geospatial representation in Australia.

A Sudden Void

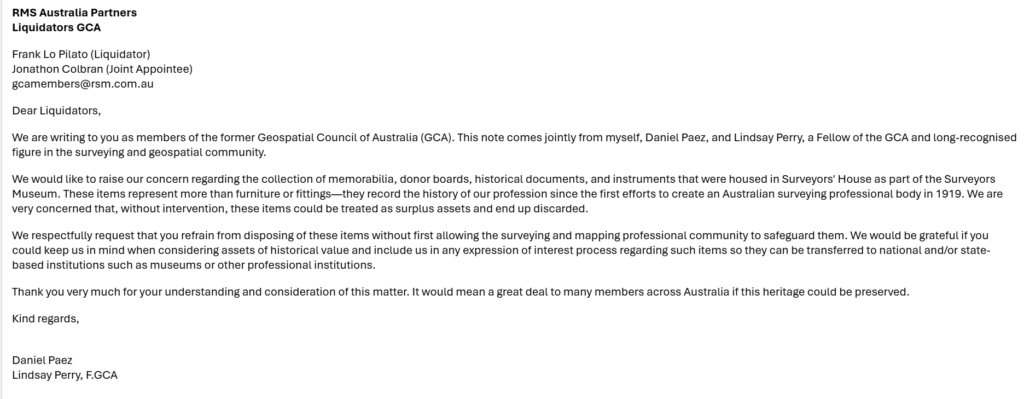

But in mid-2025, GCA went into receivership. For the first time in more than 50 years, Australia has no national professional or industry association representing the geospatial sector.

The implications are significant:

- Professionals lose a body for recognition, certification, and networking.

- Businesses lose an industry advocate.

- Government loses a clear contact point for geospatial policy and workforce development.

Conclusion: Lessons from the Journey

From ISA and AIC, through AURISA and URISA links, to SSI and finally SSSI, Australia’s professional associations reflected the expanding scope of geospatial practice. Each merger aimed to reduce fragmentation and unify the community.

The creation of GCA in 2022 was the culmination of this decades-long process. Its receivership in 2025 is therefore more than just an administrative failure – it represents the collapse of a vision to bring every part of the sector together.

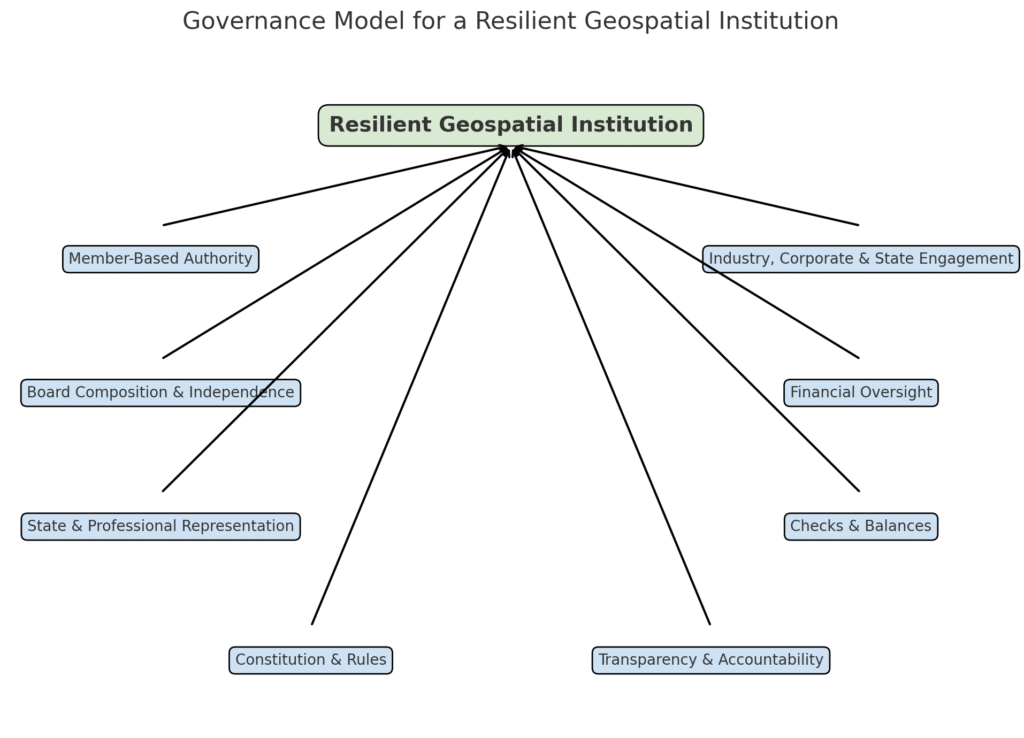

The story of our associations is one of adaptation. If history tells us anything, it’s that the next chapter will not be a simple rebuild of the past – it will need to be something new, more relevant, and more resilient.